Handover of land in Natukobenyo

As shown in Fig. 2, UNHCR has on several occasions attempted to access additional land for expanding refugee operations, first in 2003 and again in 2010. In both cases, negotiations focused on an area in the vicinity of Lokwamor and Locileta, located along the Kalobeyei River and about 20 km west of Kakuma. This site was suitable for a camp due to the presumed availability of groundwater from the river. However, Locileta and Lokwamor were also important wet season grazing areas for pastoralists, who have historically returned to the area with their cattle and goats after enduring the dry season in the more dangerous borderlands further west. Reflecting on these events, the Chief of Kalobeyei Town recalled that the government expressed an intention to negotiate, but wasted no time surveying the site and starting construction.

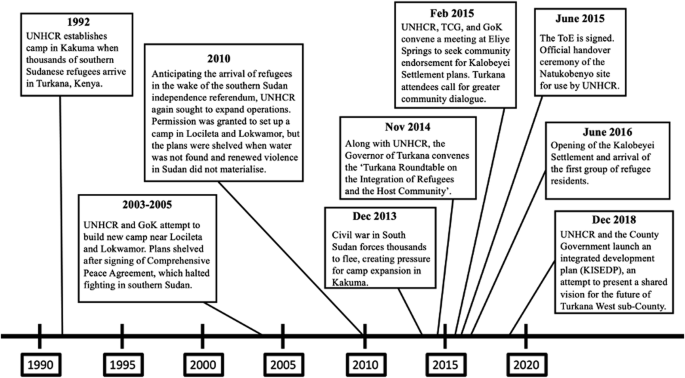

Timeline of key events in the establishment of the Kalobeyei Settlement. This timeline was assembled based on input from both FGDs and interviews as well as a desk review of relevant reports, especially the Terms of Engagement (discussed below) and the Kalobeyei Settlement Advisory Development Plan produced by UN-Habitat (2018). There is some disagreement with the Terms of Engagement document, which is dated to the opening (February 2015) of a dialogue that lasted multiple months, rather than the date when the agreement was signed

At one point – and it was unclear whether this followed the 2003-05 or 2010 attempt to gain access to the Locileta and Lokwamor sites – men gathered in Lokwamor to perform an agata, a collective chanting ritual associated more with rural traditional life than urban modernity. The agata is performed by male elders on various occasions, including weddings, initiation rites for youth, and at gatherings convened by an emuron (a recognised seer or diviner) to deal with community-wide problems such as drought or insecurity. The intention of the chanting is to impose a collective will upon the land, to bring order and coolness to tense situations and to chase out undesirable spirits, human or otherwise. Since that time, various failures and accidents have been attributed to the agata ceremony.

The old men did some curses on that land. Then, when people from UNHCR went to demarcate that land and drill water, something mysterious happened to them. Their truck sank into the soil… They failed to get water in Lokwamor because the old men of the area had cursed the land with those rituals. The engineers confirmed that there is water there, yet all the boreholes were dry! (Urban Resident, Kalobeyei Town, September 2016)

The agata was allegedly accompanied by acts of sabotage, including the removal of survey beacons and refilling of freshly dug latrine pits. In hindsight, some locals have seen these protests as successful, because no camp was ever actually established in Lokwamor and Locileta. Of course, there were other factors at play, as events in Sudan reduced the apparent need for camp expansion. In 2005, the signing of the Comprehensive Peace Agreement allowed many refugees to return to southern Sudan, significantly reducing the camp population. And again in 2011, the completion of the South Sudanese independence referendum seemed to avert another wave of displacement, thereby diminishing the pressure for camp expansion.

As of November 2013, over 127,000 refugees—most from Somalia and South Sudan—lived in the camp. That December, the start of the civil war in South Sudan forced many people to seek asylum in Uganda and Kenya. The influx of new arrivals quickly exceeded the capacity of the Kakuma camp, even as new shelters were constructed in an expanded section named ‘Kakuma 4’. In order to decongest Kakuma, the UNHCR reached out to the government to find additional territory.

However, as described above, the terms for acquiring access to land had changed with the passing of the new constitution in 2010. Rather than simply designating new territory for the settlement, a process of community engagement was convened by the National and County governments, as well as UNHCR. This process relied heavily on local ‘elites’, a term that refers to urban, educated individuals who draw influence from their connections to government and NGOs. After several failed attempts to secure access to land in Lokicoggio and Nakoyo, and recognising the persistent community opposition in Lokwamor and Locileta, some of the local elites from Kalobeyei directed the government to Natukobenyo, a site located about midway between Kakuma Town and the Kalobeyei River (see Fig. 1 map).

In February 2015, the national and county governments selected a group of elites from Kalobeyei and invited them for a meeting at Eliye Springs, a resort on the western shore of Lake Turkana. However, news of the meeting was disseminated throughout their networks, and the turnout was larger than expected. One of the uninvited attendees commented:

They [government and UNHCR] said they were coming to negotiate. In a real sense, they were coming to get an endorsement for something they had already decided at the leadership level. But when we attended and spoke up as professionals, we altered the process. (Kalobeyei Resident, Phone Interview, October 2020)

Attendees called for a more comprehensive process of community outreach. A group of professionals from Kalobeyei formed a 7-member Community Dialogue & Development Committee (CDDC), with the objective of speaking to people throughout Turkana West sub-County about the plans for the Natukobenyo site. The UNHCR appointed one member of the committee as a Community Liaison Officer, whose job was to communicate CDDC findings to the UNHCR and its partners. During the months that followed, the CDDC reached out to people across Turkana West. Discussions focused on the environmental and social impact of encampment, as well as host community complaints about access to water, health services, education and livelihoods. The CDDC used their research to inform negotiations with the UNHCR and the TCG, and an agreement was finally reached in June 2015. A document titled ‘Terms of Engagement for a 2nd Refugee Camp in Kalobeyei’ (ToE) was signed by representatives of the County and National governments, as well as UNHCR, and the Natukobenyo site was officially handed over to the UNHCR on World Refugee Day in June 2015. Relocation of refugees to the new settlement began in May 2016 and continued until June 2017, when the settlement population reached maximum capacity at nearly 40,000 people.

Barriers to local legitimacy

The ToE is the product of a dedicated effort to engage the local community in dialogue about the UNHCR’s refugee operations. In it, the CDDC put forward a long list of demands that the UNHCR agreed to incorporate into their plans for the Kalobeyei Settlement, including provision of employment to local people, the award of contracts and tenders to local businesses, and support for education and health services. A number of points focused specifically on support for pastoralism:

-

Provision of water for livestock, using dams, rock catchments, water pans, etc.

-

Support for livestock production, health and husbandry

-

Destocking and restocking programmes at appropriate seasons

-

Protection of indigenous knowledge, bio-diversity and other resources

-

Preservation and protection of dignity of cultural practices and traditions

However, interviews and focus groups conducted between 2016 and 2018 yielded many complaints that some locals had been excluded from the process and that their needs and expectations were not being met in practice. As described elsewhere (Rodgers 2020a), those engaged in pastoralism were especially disappointed.

It is important to qualify this claim with three caveats. First, the Kalobeyei ‘project’ is still only in early stages, and it is too early to make claims about overall success or failure. Second, not everyone is dissatisfied. Many entrepreneurs have built shops in the settlement. A handful of Turkana people living in the direct vicinity of the Settlement are enjoying improved access to health services, close access to well-stocked shops, and a market of refugee customers to whom they could sell firewood or locally produced charcoal. Some even received free stone houses constructed under a UNHCR cash-for-shelter programme. And finally, implementation has faced some unexpected complications. The original plan for an integrated settlement aimed at a ‘hybrid community’, in which refugees and Turkana ‘hosts’ would live together and share integrated services—schools, clinics, water utilities, etc. However, few Turkana people were willing to move into the settlement, for fear of leaving their existing neighbourhood networks and living in a place where they felt like a minority. According to teachers at the Morning Star Primary School in the settlement, by 2019 there were over 3000 refugee students but only about 10 pupils from the host community. One response was that the UNHCR widened the scope of its partnership with the TCG. Rather than restricting the project to the 15 km2 of the settlement, the partnership evolved into the Kalobeyei Integrated Social and Economic Development Plan (KISEDP). This more ambitious agenda encompassed all 1500 km2 of Turkana West sub-County, but because it no longer entailed co-residence of refugee and host communities in the settlement, integrated service delivery was complicated.

When reviewing the preliminary findings of my research with friends in Turkana, some expressed scepticism about the complaints that I was hearing. A common remark—including amongst people who were themselves Turkana—was that rural leaders have a cultural predilection during public meetings to negotiate for more, regardless of what has already been received. Others suggested that the oil negotiations in the south had set a precedent that politicised the dialogue process in Kalobeyei, creating unrealistic expectations.

Nonetheless, interviews and FGDs conducted for this study encouraged discussants to elaborate upon their complaints. The sections ahead consider some of the specific reasons that certain individuals or groups were left to feel disenfranchised by the structure of the community engagement process. They reveal that despite efforts at inclusivity by the UNHCR and its partners, the community dialogue process was compromised by poor understanding of pastoral land use and heavy reliance on urban mediators.

Contested claims to communal land

As described above, the CDDC prioritised geographical coverage in its approach to community dialogue. The membership of the CDDC was comprised of two to three members from each ward or location in Turkana West sub-County. Individuals would speak with people in their respective locations and then combine their reports at full committee meetings. This model of organisation was intended to ensure that people from all parts of the sub-County were consulted about the handover of Natukobenyo. The former chair of the CDDC emphasised the importance of incorporating perspectives from across the sub-County.

This issue of focusing on people close to the camps – we discussed this but feared it could produce a lot of animosity. If needs aren’t met, people will use force to meet them. When I was a county counsellor, there were a lot of tensions, because the host community wanted access to food aid and water. It was those living far from the camps who felt left out and took to violent methods to get their “services” from UNHCR. (Phone Interview, October 2020)

By incorporating the viewpoints of both proximal and distant people, the CDDC hoped to avoid resentment among those living far from the settlement. This also reflected the view that the land in Natukobenyo was communal and belonged to everyone. Similarly, official accounts from the TCG depict land in Turkana as a commons resource, in which ‘people are free to graze and settle in any area of their choice’ (TCG 2013: 19). On the one hand, this recognition of communal rights stands against privatisation and enclosure of pasturelands. It recognises that pastoralists require the flexibility to move their livestock throughout the territory according to the availability of seasonal vegetation. However, this particular conception of ‘communal land’ overlooks the complex social processes through which people negotiate access to different kinds of land use. Unlike conventional common property regimes, in which resources are governed by strict rules applied to clearly defined territories and groups, pastoralist land use is characterised by unbounded territories, contested group membership and negotiated access (Behnke 2018). Rather than a single coherent system, land can be governed through a ‘complex mosaic’ of rules, which are applied unevenly across scales and in regard to different resources (Robinson 2019).

From this perspective, then, Natukobenyo did not belong to any one group, but was a place where different groups had multiple, overlapping and at times contested claims. For those with cattle—who spend most of the year in the highlands of Oropoi, Nawounitos or even further west in Uganda—Natukobenyo was a source of wet season graze to which herders could return following the rainy season. In actuality, they have not returned to Natukobenyo in large numbers since 2007 because the area no longer supports the species of grass that cattle prefer. Nonetheless, herders in the FGD in Nawounitos emphasised their collective rights to places like Natukobenyo. In principle, this extends to all people of the Ng’ilukumong territorial section, who occupy a vaguely defined territory starting near Kakuma and extending westward to the border.

But residents of Natukobenyo emphasised a more exclusive claim to the area, referring to it as the place where they lived, tended goats and cultivated gardens along the seasonal streams. For this group, the handover of Natukobenyo was about more than lost pasture; it also meant that they had to leave their homes and abandon their gardens. Technically, they were permitted – and even encouraged – to continue cultivating in the area, a point that was made clear during a series of public outreach events convened by UNHCR and local chiefs. And indeed, some of the long-time Natukobenyo residents. But by July 2017, most people had chosen to move beyond the boundaries of the settlement, citing a loss of vegetation, increases in livestock theft, depletion of indigenous plant cover, and fear of insecurity at night. At the 2017 FGD that I conducted in Natukobenyo, some attendees pointed to a nearby stream where the remnants of thorn fences marked their old gardening sites.Footnote 1 In their view, they should have had the loudest voice in the barazas—the meetings called by the CDDC—but the inclusion of everyone from the wider sub-County left them drowned out by the crowd.

Similarly, participants in the Lokwamor FGD explained that they used to graze their goats along Ayanae Esikiriait, Kangura, Ayanae Elelea, and Ayanae Angidapala, all streams in Natukobenyo.

Even after the refugees arrived in Natukobenyo, our animals still grazed inside the settlement. Until they became frightened by the iron-roofed houses. We had some people from this place [Lokwamor] who were living in Natukobenyo at that time, but they returned here after the refugees were settled in that land. (Turkana Woman, Lokwamor FGD, August 2017)

Because the TCG defined Natukobenyo as a commons resource, the community dialogues encompassed the entire population of Turkana West sub-County. While admirably inclusive, this approach overwrote differences in the impacts experienced by particular individuals and groups, who drew on different combinations of goods—grazelands, gardens, residences—and would be affected differently by the settlement.

This is not to suggest that merely narrowing the geographic band of recognised households would be an adequate alternative. The relevant unit of analysis is the extended family, within which resources are shared. Most families traverse large geographical distances. Women in the Natukobenyo FGD described how their gardens sustained not only their local households, but also their relatives who had migrated west with the cattle. At the FGD in Nawounitos, herders pointed out that they had left behind and occasionally sought support from extended family members who were living in Natukobenyo.

One word that encompasses this tension between the collective land claims of the wider population with the exclusive claims of particular people is ere (pl. ng’ireria). The word is shared by several closely related and even mutually intelligible languages in the region, and its meaning varies according to differences in socio-ecological context. Amongst Karamojong agro-pastoralists to the west in Uganda, ere refers to permanent settlements organised by agnatic descent, and it approximates a claim to private property. Young Karamojong herders migrate away from the ere with their animals during the dry season and then return at the start of the rains, when grass becomes available around the settlement. However, in much of Turkana, the more arid environment has made permanent settlements impractical. Therefore, an ere in Turkana may refer not to a village, but to the general area where a herder returns during the rains. This is a more tenuous attachment to place that is less easily reduced to private property rights. It refers to collective notions of territorial belonging. During the FGD in Nawounitos, one herder explained that Natukobenyo—along with Locileta, Lokwamor, Abaat and even Kakuma—are the ng’ireria of the entire Ng’ilukumong territorial section, where they can access wet season pastures during the long rains (akiporo).

In Turkana, exclusive claims to an ere are negotiable and may be contested. They are not inalienable like private property rights, but are rather contingent on the present residence of one’s relatives as well as the graves of ancestors. Pastoralists negotiate their access to wet season grazelands in the presence of both elders and administration chiefs, who attempt to ensure that the distribution of herds will not result in overgrazing. Some herders have priority to move to a particular area because they leave behind a segment of their household, including those who are too young or elderly to be helpful in the cattle camps, as well as some women who can cultivate sorghum and maize along the small seasonal rivers. The presence of their relatives in a place may be taken as evidence that it is their ere.

Because they are so contested and open to negotiation, claims to an ere do not provide a concrete identification of ownership and are often dismissed by formal authorities attempting to arbitrate land claims. The solution of the TCG was to avoid individual or household-based land claims to Natukobenyo and focus on broad communal possession of land for everyone in Turkana West. But this geographical approach to inclusion failed to account for differences in people’s relation to—and reliance upon—the Natukobenyo site and left some groups feeling disenfranchised by the process. An alternative would be to focus less on land claims as bundles of territorialised rights and instead address the particular ways that different groups use the various resources on that land.

Oppidan bias

For people in Turkana West, the dialogue process conducted by the CDDC was a means of advocating for greater ‘host community’ benefits from the UNHCR. Through the ToE, the CDDC successfully brought the concerns of a broad swathe of Turkana society—including urban entrepreneurs, urban working class and rural herders—to the table. However, support for pastoralists was gradually dwarfed by investments in the agricultural and retail sectors. This section considers how the structure and composition of the CDDC may have contributed to the marginalisation of pastoralists’ concerns.

The CDDC was formed through a participatory process in which two local leaders were nominated from each ward throughout Turkana West sub-County. The process for nominating representatives was broadly inclusive, but inevitably the individuals most suited for a committee role fit a particular profile: urban, formally educated professionals, many of whom had previously worked for the government or NGOs. This demographic is sometimes described as the ‘elite’ class in Turkana. Some non-literate individuals were included as representatives, but not among the core 7-member committee of the CDDC. Elites are well-positioned to function as an interface between members of the public and international organisations like UNHCR. But they are also less directly involved in the everyday activities of pastoralism, and their attention is often oriented to the infrastructural and entrepreneurial projects implemented by the major development organisations.

For this reason, the reliance on elite mediation produces an oppidan bias toward a vision for development that is urban and agricultural and focused on the cash economy. Even if the community consultation process was broadly inclusive, that content is ultimately communicated through the core membership of the CDDC, who are the only individuals with whom UNHCR directly engages. This bias is not lost on the wider population; as one woman living on the periphery of the Kalobeyei Settlement explained:

Those people in town (ng’itunga lua arek) are the ones who benefit. They get jobs with the big organisations, or working for the government, or starting businesses in the settlement. We ng’iraiya just watch as our livestock are finished by drought. We just survive on the charcoal and firewood that we sell to the refugees. But these people in town have opened their shops. (Turkana Woman, Natukobenyo, Interview, September 2018)

This statement was repeated along similar lines by many interviewees in Kalobeyei. The reference to ng’iraiya rather than ‘herders’ (ng’ikeyokok) points to a social distinction that is more complicated than pastoralists vs non-pastoralists, incorporating social differentiation based on various sources of cultural capital such as formal education, linguistic competency and familiarity with urban life (Rodgers 2020b). It suggests not only that pastoralists have been marginalised, but that urban elites have enjoyed much of the benefit of the settlement. Looking at spending by humanitarian agencies in Kalobeyei, this is undeniable. For each month of 2018, a total of about 500,000 USD was received as restricted cash transfers by refugees in the Kalobeyei Settlement. The restrictions meant that these transfers could only be spent at 45 shops contracted by World Food Programme (WFP) (Betts et al. 2019). This gave a small number of refugee and Kenyan entrepreneurs a large captive market. In mid-2019, WFP began the transition to unrestricted transfers, which makes this food retail market open to more businesses. Regardless, rural herders without entrepreneurial skills are unlikely to benefit from this as much as urban residents.

Turton (2003) describes ‘two principal characters’ who often play an important intermediatory role in pastoralists’ engagement with states: the Politician and the Priest. Whereas the Priest is a customary leader whose role is integrally grounded in the herding community—often a respected seer, diviner or prophet—the Politician is a formally educated individual somewhat removed from the day-to-day activities of pastoralism. Even if they are in an appointed rather than an elected position—and thus are not ‘politicians’ in the usual sense—their suitability for the role requires that they hold the respect and trust of the communities with whom they work, as well as the linguistic ability to communicate with them. Moreover, the Politician’s formal education and professional experiences endow them with the cultural capital required to engage effectively with state institutions as well as international NGOs.

This cultural capital, however, can also generate biases. Versed in the conventional narratives of development, urban elites are more likely to commit to a vision of progress based on economic growth, urbanisation and even agricultural development. This is not an example of ‘elite capture’, in which influential individuals divert and profit from international resources intended for the community. In many cases, the problem is that elite intermediaries earnestly—and often with good intentions—buy into the vision of development presented by international institutions and their funders.

While the problem of elite bias is shared by most representative democracies, it is especially stark in places like Turkana, where the cultural capital of formal education and professional experience creates such extreme differences in interests, preferences and epistemes between an elite minority and a pastoralist majority. And if pastoralist leaders—as embodied in the trope of the Priest—do not see urban elites as legitimate representatives, they may attempt to circumvent their authority. This is illustrated in the case of the agata event described above, which preceded UNHCR’s withdrawal from Lokwamor and Locileta. During my interviews, former members of the CDDC recalled that the agata ceremony was done behind their back.

Moreover, the problem of oppidan bias does not fall solely on the shoulders of elite representatives such as the members of the CDDC. As noted above, the CDDC did recognise pastoralists’ concerns when drafting the ToE. However, the ToE was a non-binding document akin to a memorandum of understanding. It provided principles and priorities that could inform—but not determine—the course of the intervention in Kalobeyei. The ToE ultimately fed into the composition of KISEDP, a policy document specifying not principles but concrete projects and objectives. There is some support to pastoralism under Component 6 of KISEDP, which is titled ‘Agriculture, Livestock and Natural Resource Management’. It includes a short list of strategies to ‘increase livestock production and productivity’, such as establishing water points along migration corridors, reseeding of pasturelands and seasonal restocking of herds. However, to date, there has been little actual investment in these strategies. Moreover, some of the listed strategies, such as digitising the livestock branding system and ‘modernising’ slaughter systems, are low on the list of priorities of herders. The key indicators for Component 6 of KISEDP all pertain to agriculture, with no indicators by which to assess support for pastoralists.

The problem, in this case, was not only that urban professionals led the community engagement process, but that the actual engagement with the public was reduced to an initial phase preceding the ToE. As the ToE was operationalised in the form of KISEDP, UNHCR and the TCG took the lead, with some input by the CDDC. But there was almost no involvement by the wider Turkana population as these plans evolved, and so pastoralist priorities gave way to the oppidan model of development. This is perhaps best captured by a short section in the introduction of the KISEDP document, which begins by noting that pastoralism is practised by approximately 65% of the county population, but then depicts trends of change and transition:

Poorer households are either ‘dropping out’ of pastoralism or choosing alternative livelihood options, relying more heavily on food sources such as food aid, payments in kind, crops and wild foods, and to rely on (sic) safety nets, crop sales, self-employment and casual employment as income sources. In particular, many Turkana young men and women no longer only want to become pastoralists and they often seek to combine a nomadic lifestyle with an education and/or employment opportunity. (UNHCR 2018: 10)

The suggestion is that pastoralism is a way of life that is no longer viable and is now on the wane. This corresponds to familiar narratives of sedentarisation and transition that have influenced development in pastoralist areas for decades (Krätli et al. 2015). An alternative framing that emphasises the continued significance of pastoralism despite increasing social stratification, urbanisation and livelihood diversification would be equally consistent with the cited data.

GIPHY App Key not set. Please check settings