1. Introduction

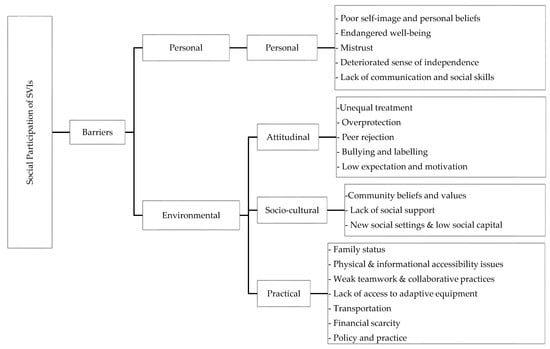

Social participation is key to human beings and a remedy for social isolation [1]. It encompasses an individual’s involvement in a variety of formal and informal activities [2,3] “ranging from working for organisations to inter-personal and friendship activities” [4] (p. 448). Social activities enhance quality of life, health, wellbeing, self-esteem, and social and cognitive skills [1,2,5,6,7]. The nature of the activities involved and the participant’s age determine the benefits one may obtain from social participation. For instance, while social participation helps children to develop social skills and knowledge through interactions [5], it also improves health for older adults [2,8], and significantly impacts dimensions of identity in adolescence and emerging adulthood [9].Despite the range of advantages that social participation provides, not everyone in a society has equal access and opportunity to participate [10]. Historical accounts have shown that people with disabilities (PWDs) were generally among the socially excluded groups [11]. Some exclusionary practices included hiding, forsaking, and killing children with disabilities [11,12]. Similarly, people with visual impairments (PVIs) (including students with visual impairments (SVIs)) are commonly reported to have lower social participation and face a great risk of sociocultural exclusion from everyday life activities [13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22].Previous studies discuss various personal and environmental factors that restrict individuals’ social participation, including functional abilities, skills, and personal interests, as well as cultural, physical, social, and institutional environments [23]. Yet, some shortcomings have also been demonstrated in the social participation literature as most research on the topic focuses on the participation of older and retired adults (e.g., [1,24,25]), or on certain activities, such as physical activities (e.g., [26,27]) in school settings (e.g., [28,29]), and in formal services. However, little attention has been paid to individuals’ participation in the community (e.g., [30]). Notably, most empirical evidence mainly concerns the conditions of PWDs in the global north, although 80% of them live in the developing world [31], especially in Africa.Additionally, although the impacts of participation on health, wellbeing, socio-economic status, and quality of life have been well documented [32,33,34,35,36,37], the findings’ implications have rarely been explained against cultural contexts. Considering the cultural dimension is essential, especially in disability studies [38], as society’s beliefs considerably shape norms, values, attitudes, and the reality for PWDs. Culture influences social relationships and interpretations [39] and determines perspectives on what disability is and how PWDs are treated [40]. It provides context to understand PWDs’ disabilities and participation in a given society. In Ethiopia, the belief that disability is a punishment from God for one’s parents’ sinful deeds [41] may be used to justify the exclusion of PWDs [42]. Cultural beliefs also affect the early identification of and interventions for children with disabilities [43]. The theoretical resources for the cultural model of disability espouses that “disability cannot be taken as a given but that its meanings must be understood as inherently part of culture” [38] (p. 6).Moreover, the implications of cultural orientation as an individualist and collectivist culture in studying social participation may provide additional clues on the severity of outcomes. Individualism–collectivism is one of the dimensions that help explain cultural differences [44]. In an individualistic cultural context, individuals are deemed to stand independently and have distant social relationships. In contrast, social relationships, roles, and status are the defining elements in collectivist cultures [45,46]. Ethiopia is culturally highly collectivistic, involving group obligation and relationships to subdue individual interests [47]. Subsequently, being stigmatised in a collectivistic cultural context usually has adverse relational impacts because, in this cultural reality, norms determine relationships and are enforced without explicit communication. Ethiopia, a country with a high-context (collectivist) culture, tends to have more implicit and vaguer verbal and non-verbal communications, powerfully controlling individual society members in many subtle ways [47] and impacting social interactions and participation. For those with disabilities, this situational circumstance often presents additional difficulties in hindering their meaningful communication and social engagement.Because social life and relationships are more valued in a collectivist cultural context [46,48,49,50], the feelings social deprivation creates would ostensibly be more intense. Beyond the direct disadvantages of inadequate social resources, the meaning and value attached to social worth (in the context of collectivistic culture) can cause psychological trouble. To this effect, empirical evidence shows that culture impacts individuals’ psychological processes [51], identity, and personality [52]. This might imply that (a) cultural context highly influences the participation of exceptional groups in a society; and (b) there is bitterness of social exclusion for individuals in a collectivist culture, in which social relations, support, and interdependence are essential.Given the critical impact of culture on the health and wellbeing of participants, the present study aimed to explore the barriers to social participation for secondary SVIs in Ethiopia. A secondary school setting encompasses more social interactions [53] and (even in the best of circumstances) is one of the most difficult settings involving intense biological and social pressure on students [54]. Given these perspectives, this study focuses on the experiences and perceptions of secondary SVIs regarding their participation in structured and unstructured social activities in and out of school settings. The findings are discussed in relation to the collectivist cultural context in which the participants are acculturated.

4. Discussion

Ethiopia is culturally collectivist [47], and maintaining relationships is highly valued [50]. In a collectivist culture, emotions are linked with assessments of social worth and connection—not with individuals’ inner world and subjective self, as in individualist cultures [46]. Culture influences personality [50] and is crucial to shaping interactions and behaviour and informing decisions [59], which are all critical to social participation. An individual’s worldview (which is hugely culturally formed) determines preferences for participation [60]. Thus, culture provides a lens through which individuals view themselves and others, which is crucial to social engagement, especially in a collectivist cultural orientation.Most participating SVIs developed self-doubt in many areas of their lives, affecting their social networks and participation at home, school, and community. Although negative self-perception and its behavioural impact among young people with vision impairment has research evidence [53], in a collectivist culture—where social adjustment and interdependence within groups are eminent [50]—the severe impact of social exclusion has been rarely discussed. The visually impaired participants’ assumptions about how others would perceive them and their attendant feelings of embarrassment limited their participation in sports and arts activities [60]. In a collectivist cultural orientation, emotions are emerged, embedded, and reflected as relational phenomena [46], and the kinds of relationships one has influence emotions and attendant actions. In this case, self-perception in a culturally collectivist society was affected by relational feedback, which further impacted other areas of life, including social participation. Poor self-esteem [61,62], insecurity, stress, and life dissatisfaction severely hindered social participation. Stress is negatively associated with participation in social and leisure activities [63]. SVIs’ low level of independence was reported to affect their social participation as a personal barrier. In a collectivist culture, people generally are less independent and likely to maintain the will of in-groups [49]. The fact that social interdependence is a defining element of a collectivist culture suggests that visually impaired people’s lack of independence might not only be associated with their impairment [49]. Individuals in such contexts prefer maintaining relationships to acting and accomplishing competitively [48,50].The community’s negative attitudes toward PWDs in Ethiopia, including those with vision impairments, has earlier research evidence [64,65,66]. Multiple studies show that students with special needs experience more negative attitudes in school settings than those without impairments. Harassing behaviours and bullying of students with impairments by their non-disabled peers are among the commonly reported negative attitudes affecting social participation at school [67,68].The influence of culture on forming attitudes, opinions, and personalities has been well documented [50,69,70], and non-disabled peers, teachers, family, and community members might learn to behave as they do toward SVIs through socialisation since childhood as normative behaviour. Notably, people with collectivist values tend to conform to the existing norm, as members are relationship-oriented and value group harmony [48,50]. Low levels of expectation and motivation in SVIs contribute to their social disengagement as attitudinal barriers. Similar findings also show the positive association between PWDs’ levels of expectation and confidence [71] and the latter’s impact on social participation [61,62].In this study, community, societal, and cultural values remarkably restricted SVIs’ social participation. In this regard, Rao et al. [72] noted that variations in stigmatising attitudes across different cultures might be interpreted through cultural characteristics. Participants highlighted how misconceptions about disability as a punishment for sin limit their social participation. Other studies’ findings reveal that erroneous community beliefs and values are the most daunting social challenges to PWDs in Ethiopia [73,74,75]. Unlike in an individualist culture, where disability is considered a physical and individual phenomenon and a chronic illness seeking remedy, in a collectivist culture, it is viewed as a spiritual and group phenomenon that must be accepted [76]. It is reasonable to assume such perspective differences might influence other areas of life activities for PWDs, including social participation.This study’s findings indicated that SVIs suffered from a lack of social support across settings, which hugely impacted their participation, echoing previous studies that found that poor social support is an environmental factor that adversely impacts social participation [63,77]. Support, particularly from peers, is crucial for enhancing self-esteem and social acceptance [78]. As social support and relationships are more valued in a collectivist cultural context [46,49,50], SVIs’ resultant feelings due to rejection and isolation might be severe. This suggests that more research is needed to understand what it feels like to be socially marginalised in different cultural orientations.Family socio-economic conditions put SVIs at elevated risk of having restricted social participation. Family status is a crucial predictor of social participation in impaired youth [63,79,80]. It is significant to note that due to the financial, psychosocial, and physical burden of caring and assisting disabled family members, families often encounter multiple limitations [81], adversely impacting caretakers’ social participation.The lack of accessible information about leisure activities and events hindered SVIs’ social participation. A previous study also indicated that inaccessible communication and information systems hindered participation opportunities [82]. This study provides evidence that physical inaccessibility and adjustment difficulties are significant practical barriers to SVIs’ social participation across settings [83].This finding reveals that due to their design and construction, indoor and outdoor facilities—such as public institutions, transportation services, and footpaths, among others—are difficult to access for people with visual impairments in Ethiopia, negatively impacting social participation. The data also showed that transportation is a major practical barrier hampering mobility and participation in Addis Ababa. In support of this, the literature reveals that access and transportation facilities play critical roles in social participation [77].SVIs’ lack of social and adaptation skills practically limited their social participation. Supporting this finding, another study revealed that children with vision impairments experience difficulty in forming and maintaining relationships [18,84]. Results of previous studies indicate that assuming social skills determines children’s acceptance [83], social engagement, and participation [18], and its deficits lead to exclusion from social and educational activities [85]. As cultural characteristics influence children’s social skill development [17], concerns should be taken regarding the multifaceted impact of underlying cultural values on relevant skill development and participation.The current study reveals that poor policy implementation and institutional malpractice negatively affected SVIs’ social participation. Introducing unexecuted policies regarding PWDs alone has brought no change in Ethiopia [86]. Similarly, the findings showed that institutional malpractice in providing appropriate service for PWDs limited participants’ opportunities to participate. Prior assessments in the context of Africa revealed that cultural perspective influences perceptions of disability and shapes the kind of services delivered in Africa [40]. Hence, cultural norms affect the pattern of participation or perceptions toward PWDs and the services provided, including early identification and rehabilitation [43].

The major limitation of this study is that it is based on scarce information generated from a small sample of participants, which may raise questions about the findings’ generalisability. Consequently, future research should consider gathering additional data from more participants (SVIs and stakeholders) from school and community settings.