By: Guest Authors

January 31, 2018

About the guest authors

This is a guest post by Anastasia Bow-Bertrand, Kristine Briones, and Marta Favara from the Young Lives study at the University of Oxford.

Over the past two decades, the Ethiopian government has shown a strong commitment to education sector development, making significant strides in terms of access to education and opportunities to learn. This endeavor has received global attention. In 2008, Ethiopia was identified in the Education for All (EFA) Global Monitoring Report1 as one of the countries that has seen the most rapid progress towards the Framework for Action goals agreed in Dakar in 2000, notably universal enrollment and gender parity at the primary level.

But challenges remain. Student transition to higher grades remains limited, particularly among children from the most disadvantaged groups. Late enrolment often figures alongside intermittent progress through grades and has become a barrier for meeting age-appropriate targets (with individuals becoming classified as ‘over-age’ for grade) for primary completion and progression to secondary grades. This is compounded by poor system performance and, consequently, to poor learning outcomes, so doing little to encourage students through the school gate.2

The Young Lives study has been core-funded by the UK’s Department for International Development and aims to provide policy-relevant findings over the life course of children living in poverty, in line with the global sustainable development agenda. Since 2002, Young Lives has followed the lives of 12,000 children in two age cohorts (4,000 ‘Older Cohort’ children born in 1994/95 and 8,000 ‘Younger Cohort’ children born in 2001/02) from different social, religious, ethnic and language groups across rural and urban sites in four countries, including Ethiopia.

In Ethiopia, the Young Lives children have grown up in the wake of national education reform. In 1994, the government introduced its first education policy that set out the subsequent expansion of formal schooling in the country, coinciding with the birth year of the Older Cohort. While Young Lives is not intended to be nationally representative, with over-sampling of poorer children, the sample is still able to capture Ethiopia’s diversity across regions and within a range of children.

Through its unique multi-cohort design, Young Lives data permit exploration of the determining factors of educational progress (individually and nationally) and cognitive development over a crucial period in the history of the Ethiopian education system. Furthermore, the five rounds of data collection span the children’s education cycle from the age of primary-school enrolment to an age when they typically make their transition into tertiary education (or they have already dropped out of school) and enter the labour market, so offering a rich insight into the drivers, motivators and influences on educational trajectories over a 15-year period.

In this blog we document and discuss six stories and challenges for education in Ethiopia as told through Young Lives data. Please note that while the visuals below are static, they can be clicked on, taking you to the dynamic data visualizations on the Young Lives website. There, you can also explore more of our findings and data (which is publicly available through the UK data archive).

The potential of quality early childhood care and education (ECCE) to transform young lives is now widely recognized in research, policy and service delivery. With a global focus, the United Nation Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) Target 4.2 states that, by 2030, countries should:

Ensure that all girls and boys have access to quality early childhood development, care and pre-primary education so that they are ready for primary education.

The Young Lives data captures the state of pre-school enrolment in Ethiopia study sites in 2006, when the pre-school system was still emergent.3 Only 25 per cent of Young Lives children (overwhelmingly from urban-based households) were enrolled in pre-school, predominantly in private kindergartens. Only 4 percent and 8 percent of children from the bottom and middle wealth index tercile attended pre-school.4 5

Tracking these children has shown that those who attended pre-school have better numeracy skills than non-attenders at both the age of 5 and 8 and the gap tends to increase as children grow older. Differences between pre-school attenders and non-attenders (for example in terms of socio-economic background, and investments in human capital) play a significant role in explaining the gap in numeracy test scores. Nevertheless, the existence of this gap is not wholly explained by these factors so further exploration of the positive role of pre-school for skills development is warranted.

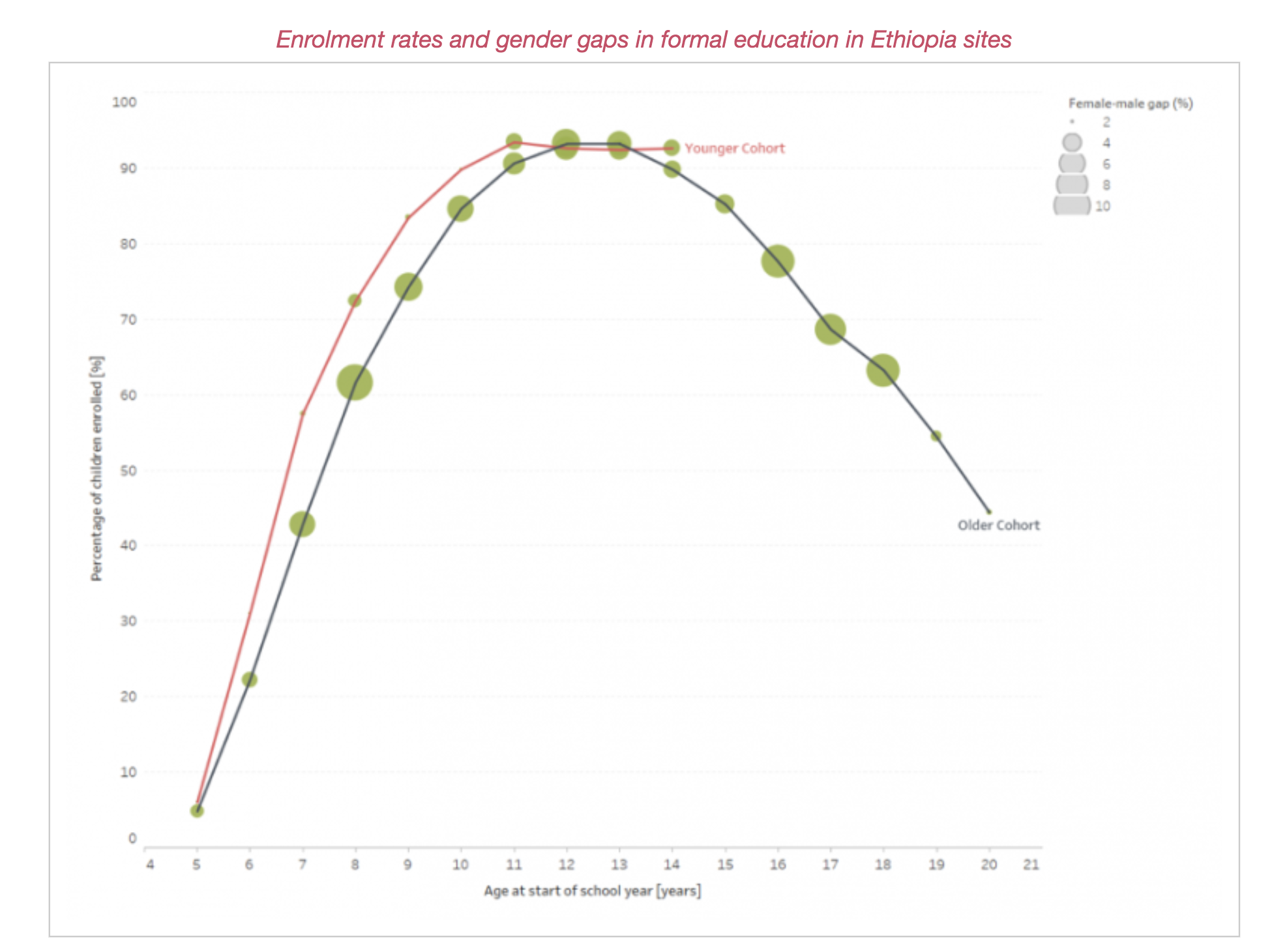

Formal education in Ethiopia begins at age seven. However, late enrolment is pervasive. The graph below shows the average enrolment rate in formal education for the Younger and Older Cohort children, at different ages.

In both cohorts, more girls than boys are enrolled at all ages. This gender gap in enrolment is represented in the chart with circles (i.e. the bigger the circle, the more girls than boys are enrolled in formal education).

Enrolment rates and gender gaps in formal education in Ethiopia sites

Enrolment rates and gender gaps in formal education in Ethiopia sites

Less than half of Older Cohort children start schooling at the age of seven. This rate increased by 14 per cent for Younger Cohort children at the same age, seven years later. However, only 57 per cent of these were enrolling ‘on time’ in terms of formal age for grade. An upward trend in the enrolment rate after the age of seven in both cohorts suggests that children are starting school late. Wealth, social capital, level of maternal education and ownership of land are among the factors that were found to have a positive impact on whether Older Cohort children were enrolled in school by the age of 7/8.6

The chart above shows that enrolment peaks at the age of 12/13 at 93 per cent for both cohorts, and starts declining at the age of 14/15 when children are expected to be in their last year of primary school (however, this is not always, as we will show below, with some individuals in the right grade for their age). This is also the age when the pro-girl gender gap starts widening and, by the age of 18, 9 per cent more girls are enrolled than boys.

Indeed, girls are more likely to progress in their education and complete secondary education than boys. The main reason for this lies in the division of labor, which in Ethiopia is markedly gendered: girls primarily carry out domestic work within the household and boys tend to predominantly work outside the household, mainly in herding or farming activities.7 Staying in education can, therefore, be a more expensive choice for boys than for girls who can generally arrange their school and in-household responsibilities more flexibly than boys.89 Absenteeism is a precursor to drop-out, often linked to poor progress and performance. The most common reason given for boy absenteeism and drop-out is their involvement in paid or unpaid domestic/agricultural work, whereas for girls this is most commonly attributed to the need to care for younger siblings.10

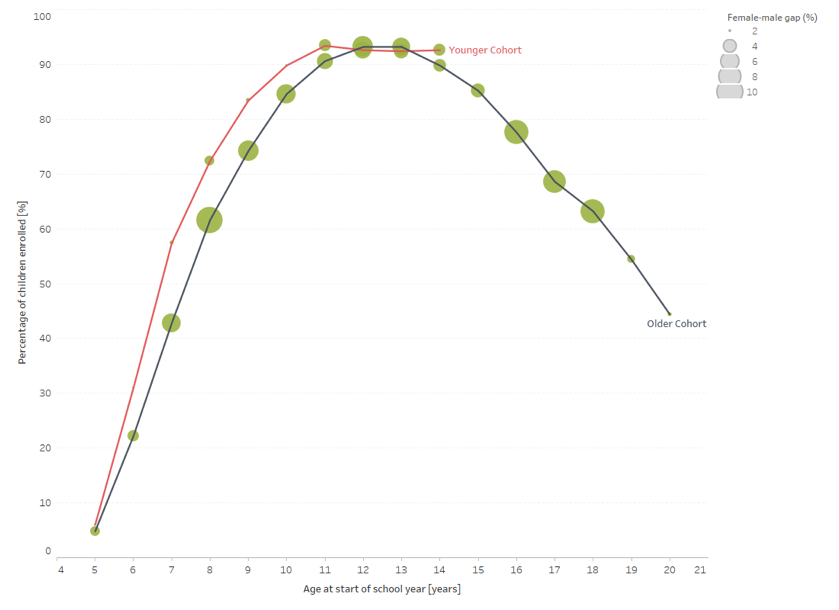

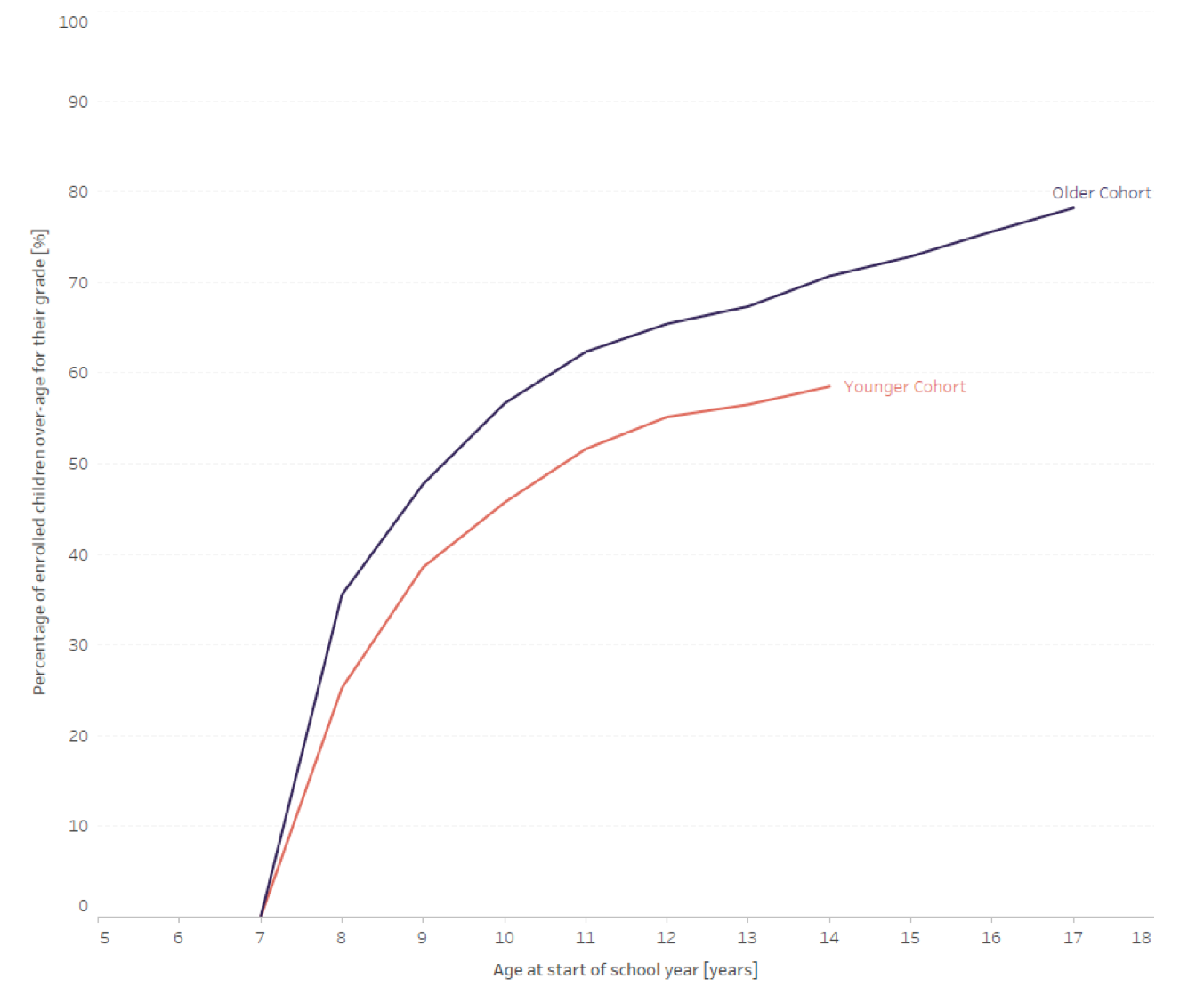

The chart below visualizes the percentage of Younger and Older Cohort students who are over-age for grade (older than the official entrance age for each grade). Late enrolment combined with slow progression through grades results in delayed education trajectories for those children who remain within the education system.

Over-age for grade in Ethiopia sites

Over-age for grade in Ethiopia sites

At the age of 15, when students should leave primary education and transition to secondary education in Ethiopia, only 27 per cent of Older Cohort children progressed as expected. On average, of this group at age 19, when it would be expected that they enter university education (following over 12 years of schooling), most have only completed 8–9 years of education. This is not surprising given the prevalence of over-age enrolment in primary education.

However, this is not the only factor explaining the high prevalence of over-age Ethiopian students. The bulk of delayed students increases year on year, signaling a cumulative delay, i.e. a slow progression through grades. Many factors can be posited, including grade repetition as linked to poor performance or absenteeism, re-entrance after a period of non-enrolment, and other circumstances. This pattern of increasing incidence of over-age students is similar for both males and females with more males being over-age for grade compared to females. Again, this could reflect competing responsibilities out of school.

The good news is that the prevalence of over-age students decreased in the 7-year period between the Older and Younger Cohort children. Nevertheless, the percentage of enrolled children who are over-age from the bottom wealth tercile has remained the same, as shown in the graph here.11

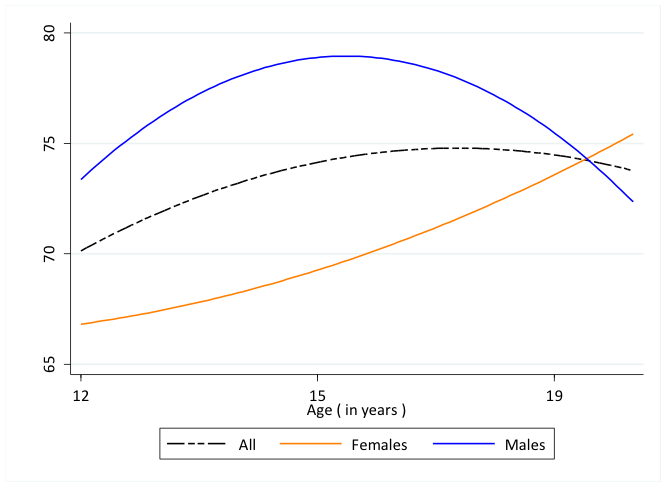

Young Lives children have high hopes for their education, as the chart shows. Each point in the graph corresponds to the proportion of children aspiring to go to university at age 12,15 and 19, including both those enrolled at school or no longer at school.

Proportion of boys and girls aspiring to university at ages 12, 15 and 19 – From: Favara, 2017.

Proportion of boys and girls aspiring to university at ages 12, 15 and 19 – From: Favara, 2017.

At the age of 12, 73 percent of children aspire to complete university. However, children living in the poorest families have substantially lower educational aspirations than children from the less poor households. So too, aspirations decrease as children grow up. Between the ages of 12 and 19, children’s aspirations change significantly and they tend to adjust their aspirations downward in line with their lived reality and their perception of the opportunities available to them.9 There is a marked inflection point at the age of 15, the same age at which the drop-out rate increases. Notably, after the age of 15, the gender gap in aspiration shifts in favor of girls, mirroring the higher drop-out rate among boys after the age of 15.

Learning levels have not increased in tandem with enrollment. Comparing Older Cohort with Younger Cohort 15-year-olds reveals that there has been no overall improvement in learning levels.12

Considerable disparities between socio-economic groups emerge when comparing children from bottom wealth tercile households with their peers, in favor of the latter. The poor quality of many school play a major role. To read more about the education system and findings on the quality of the learning environment, please see the Young Lives School Effectiveness survey.

On the right track, but momentum must continue

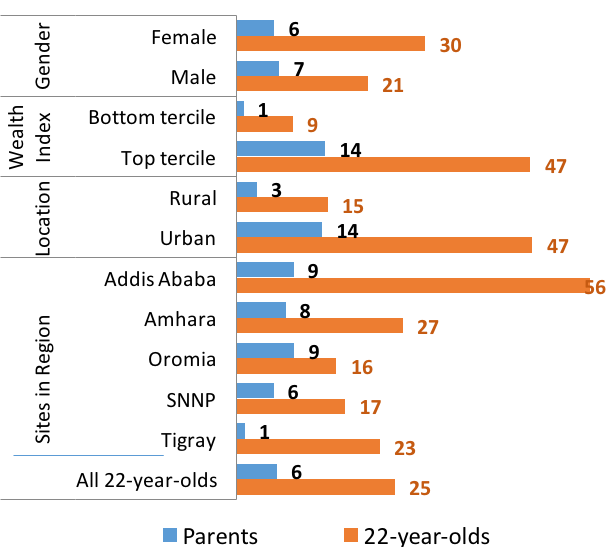

While grade progression remains slow, learning poor, and aspirations frequently unmet, there has also been noticeable intergenerational progress between Young Lives children and their parents, at least in children attaining higher school grades. The chart below compares the percentage of Young Lives parents and children who achieved post-secondary education across a number of sub-groups defined by gender, socio-economic status, location and region of residency. On average, 25 percent of 22-year-olds are currently enrolled or have finished post-secondary education compared to 6 percent of their parents.13 Once again, the greatest improvements are documented among individuals from better-off households and those in urban sites.

Percentage of Young Lives 22-years-olds and their parents who completed post-secondary education (%)

Percentage of Young Lives 22-years-olds and their parents who completed post-secondary education (%)

Find more information on the work of the Young Lives study:

As the Young Lives study reaches its final phase of core-funding, we are drawing together our education findings from Ethiopia and across all study countries to define principles for policy and programming, available here.

The above discussion draws on Young Lives data from all five survey rounds. For data visualizations and interactive delineations of this dataset, please visit our website and follow developments @yloxford with #YLdataviz and #YLEducation.

Cite this work

Our articles and data visualizations rely on work from many different people and organizations. When citing this article, please also cite the underlying data sources. This article can be cited as:

Guest Authors (2018) – “Learning for our Millennium? The changing face of education access, quality and uptake in Ethiopia” Published online at OurWorldInData.org. Retrieved from: ‘https://ourworldindata.org/education-in-ethiopia-yl’ [Online Resource]

BibTeX citation

@article{owid-education-in-ethiopia-yl, author = {Guest Authors}, title = {Learning for our Millennium? The changing face of education access, quality and uptake in Ethiopia}, journal = {Our World in Data}, year = {2018}, note = {https://ourworldindata.org/education-in-ethiopia-yl} }

Reuse this work freely

All visualizations, data, and code produced by Our World in Data are completely open access under the Creative Commons BY license. You have the permission to use, distribute, and reproduce these in any medium, provided the source and authors are credited.

The data produced by third parties and made available by Our World in Data is subject to the license terms from the original third-party authors. We will always indicate the original source of the data in our documentation, so you should always check the license of any such third-party data before use and redistribution.

All of our charts can be embedded in any site.